The Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site consists of a 24km length of the lower Derwent Valley in Derbyshire in the East Midlands of England stretching from Matlock Bath in the north to Derby City Centre in the south.

It includes within its boundaries a series of historic mill complexes, river weirs and associated settlements and transport networks. It combines elements of both a relict or fossil landscape in which the evolutionary process of industrialisation came to an end, leaving significant distinguishing features visible in material form, and a living landscape with significant evidence of its further evolution over time. Due to the nature of the site, the ownerships and interests are numerous, especially within the urban areas.

5.1 Identification of the Derwent Valley Mills

| Country | Region | Property | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | Derbyshire in the East Midlands | Derwent Valley Mills | Latitude: 53.01’ 13’’N Longitude: 01.29’ 59’’ W |

1.5.1 Identification of the Derwent Valley Mills

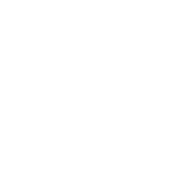

1.5.1.1 The Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site in context with other UK mainland World Heritage Sites (2020)

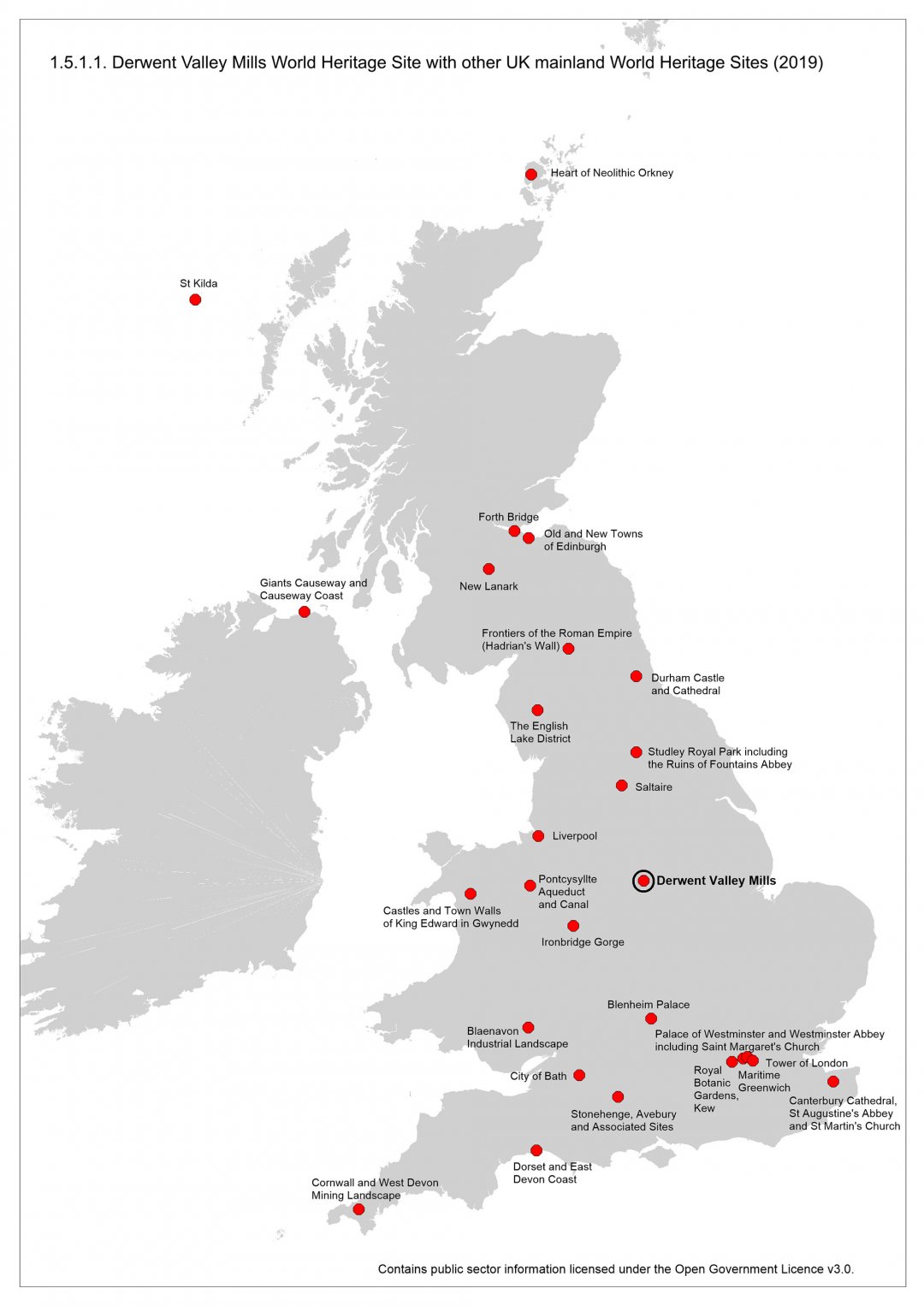

5.1.2 The DVMWHS in context – nationally and regionally

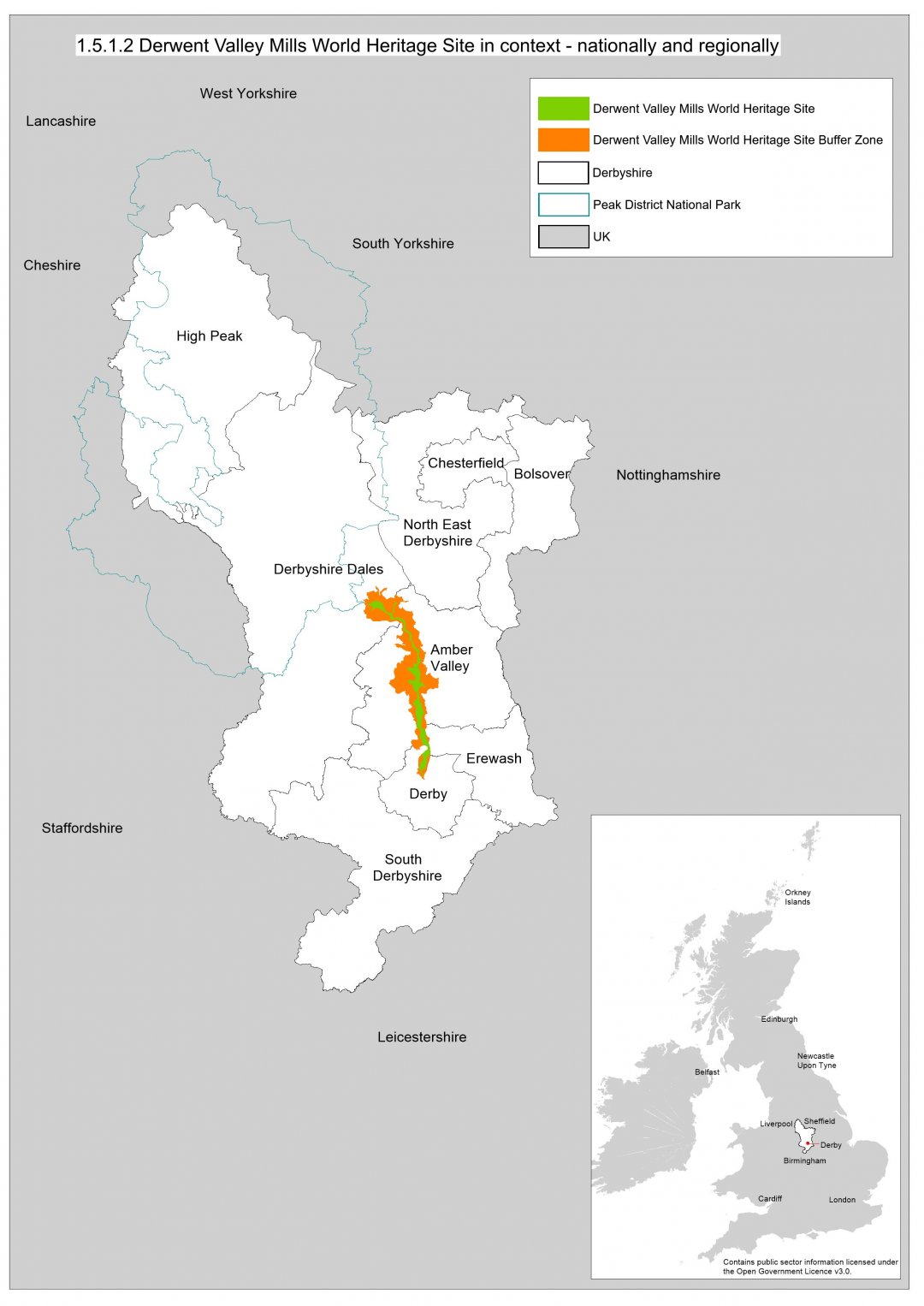

5.1.3 The Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site and Buffer Zone

5.2 Boundary of the World Heritage Site

The boundary of the site was defined through field observation by applying the following principles:

• definition of the extant historic topography (buildings, features, landscapes) derived from, and exemplifying, the historical theme of the innovation of the textile mill and the economic and social infrastructure of the site as the ‘cradle of the factory system’;

• coincidence, wherever possible, with existing statutory and other formal designations within administrative areas where these are relevant to the criteria for inscription, taking account of historical ownership but omitting any contiguous zones of different character, or significant areas where the character and/or archaeological integrity has been lost or degraded;

• delineation as a single entity, without detailed outlying elements, linked by linear features where these are the defining characteristic of the historic topography and contribute to the site’s universal value;

• tests of authenticity applied in relation to the historical evolution of a cultural landscape with particular regard to the archaeological integrity of form and landscape character, rather than necessarily the outward appearance of individual buildings.

• particularly at the southern end of the WHS, the extent of the flood plain was utilised to form the WHS boundary.

The need for a minor review of the site boundary has been identified, to provide greater clarification to the original map work of 2001, and make small adjustments where buildings or structures have been omitted or included, close to the boundary. The DVMWHS Partnership believes, with 17 years’ greater understanding of the Property, there are omissions/inclusions which run contrary to the reasons for the boundary’s original line. A formal request to UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee for a Minor Boundary Modification will take place during the lifetime of this Management Plan (See Objective 1.13 on page 66).

5.3 Map descriptions (including Buffer Zone – see 1.5.4)

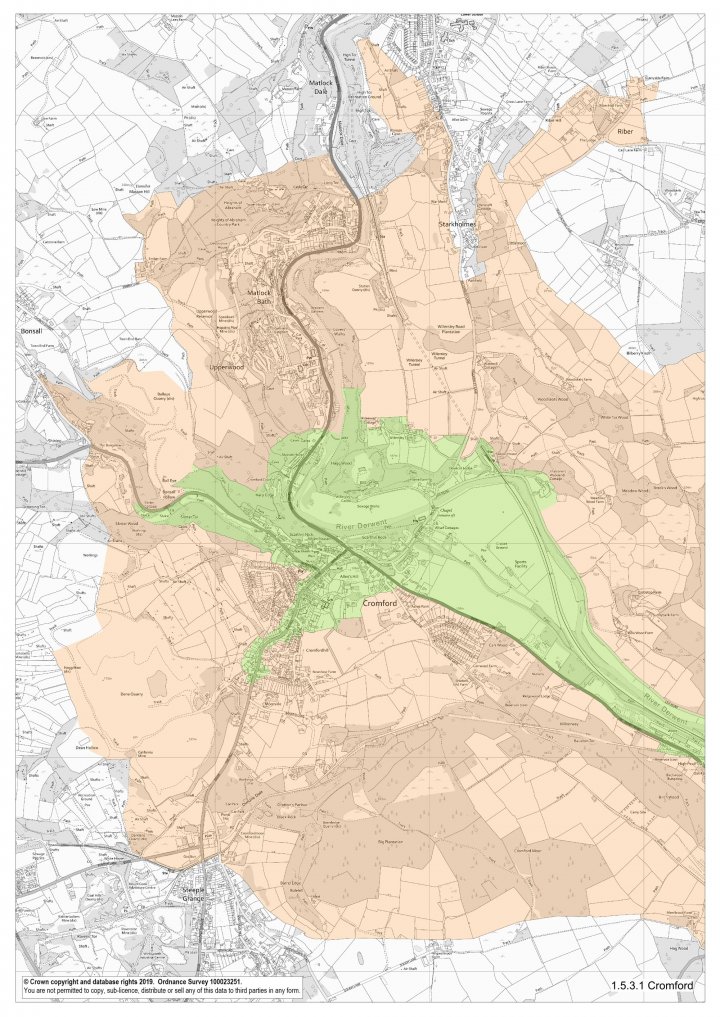

5.3.1 Cromford (Map 1)

The northern end of the site comprises the Cromford Conservation Area, which focuses on the Cromford Mills and associated water courses, Masson Mills, workers’ housing, the Greyhound Hotel, the Market Place, Corn Mill, Canal Wharf and the two Arkwright family residences and grounds. The only part of the Conservation Area to be excluded is a pre-Arkwright area of settlement to the south-east.

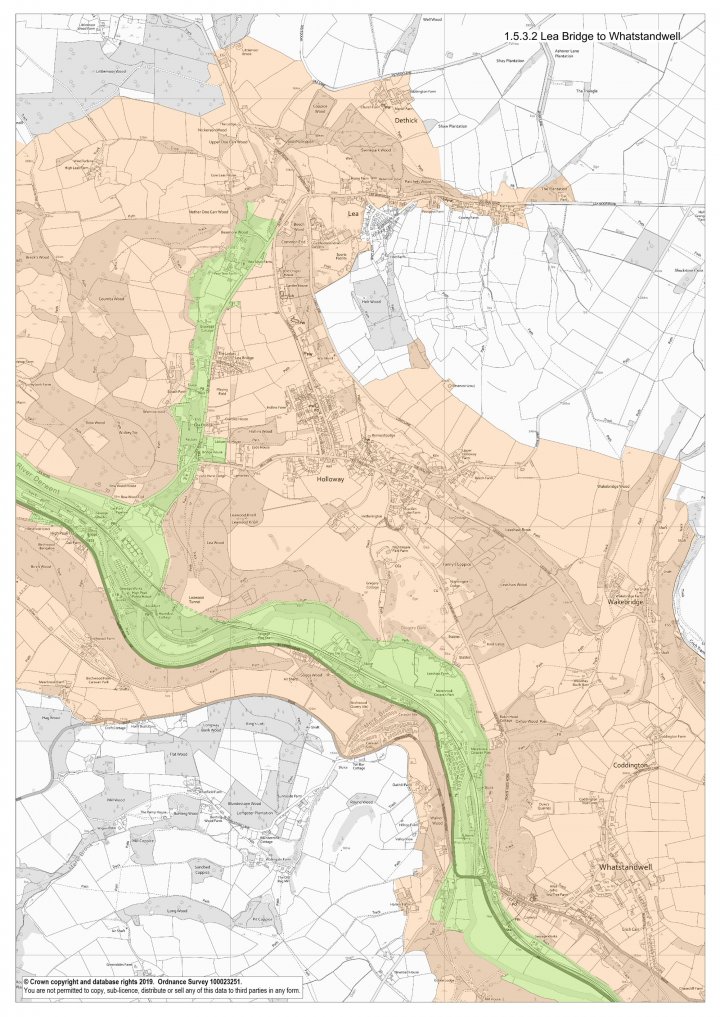

5.3.2 Lea Bridge to Whatstandwell (Map 2)

The eastern boundary follows the limits of the flood plain of the River Derwent. It is defined to the west by the Cromford Canal and a former turnpike road (now the A6). It broadens out and takes in the High Peak Junction Wharf. Further south, a short spur follows the Nightingale Arm of the canal to Lea Bridge to take in the wharf, Nightingale’s mill, terraces of workers’ housing and the water courses for the mills as far as Pear Tree Farm.

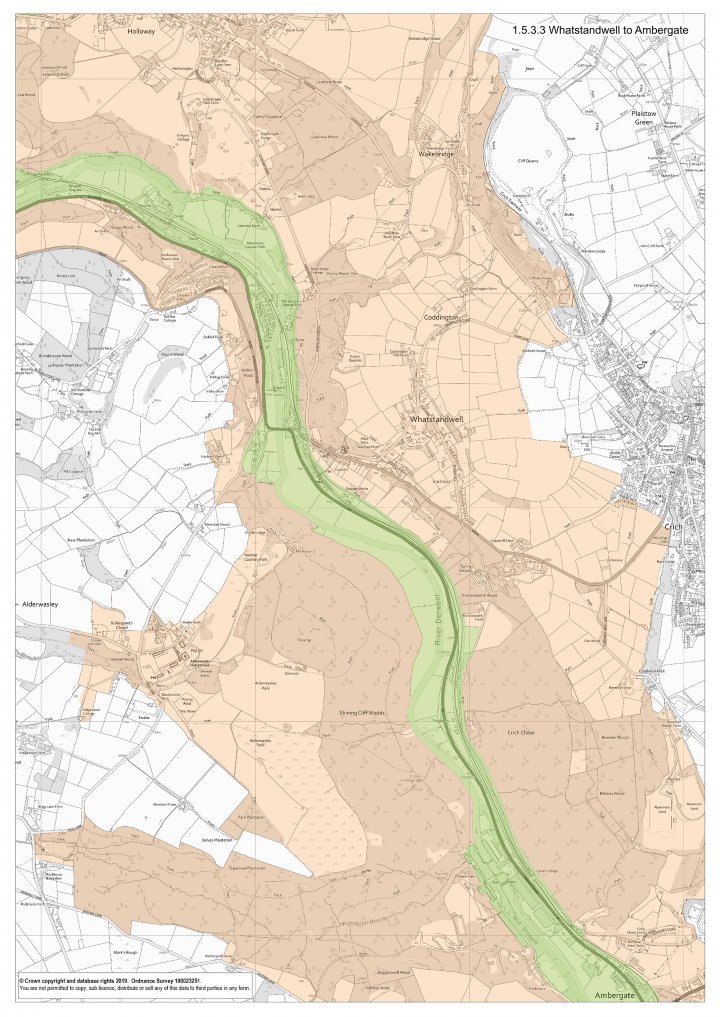

5.3.3 Whatstandwell to Ambergate (Map 3)

South of the aqueduct, as far as Ambergate, the area consists of the River Derwent, the Cromford Canal, and the former turnpike road linking Cromford to Belper and the railway line.

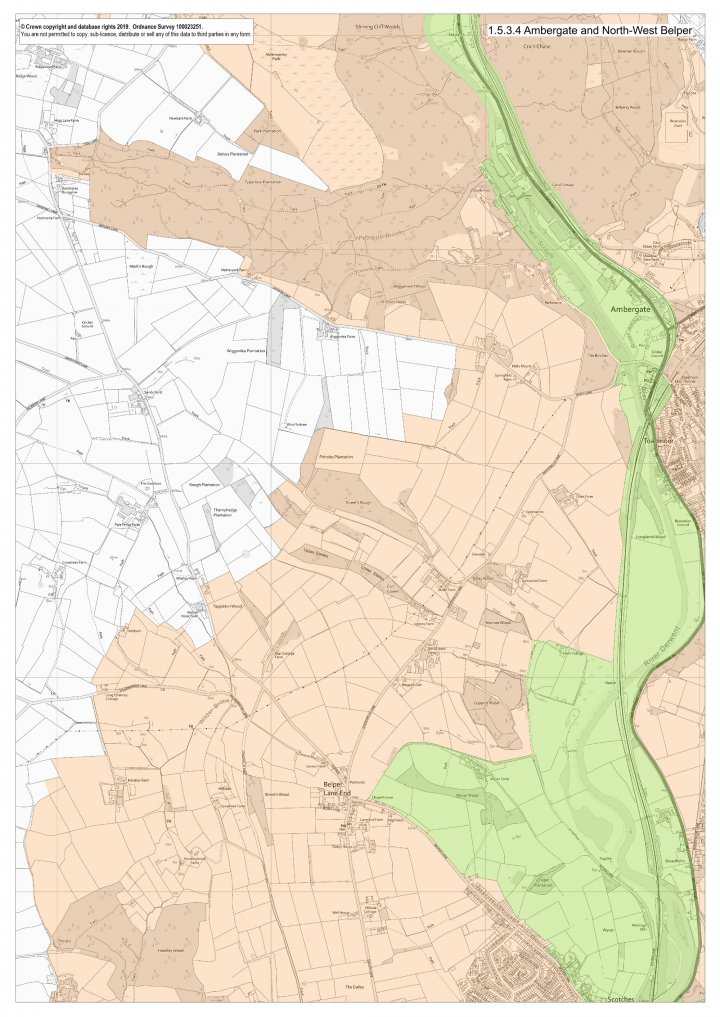

5.3.4 Ambergate and North-West Belper (Map 4)

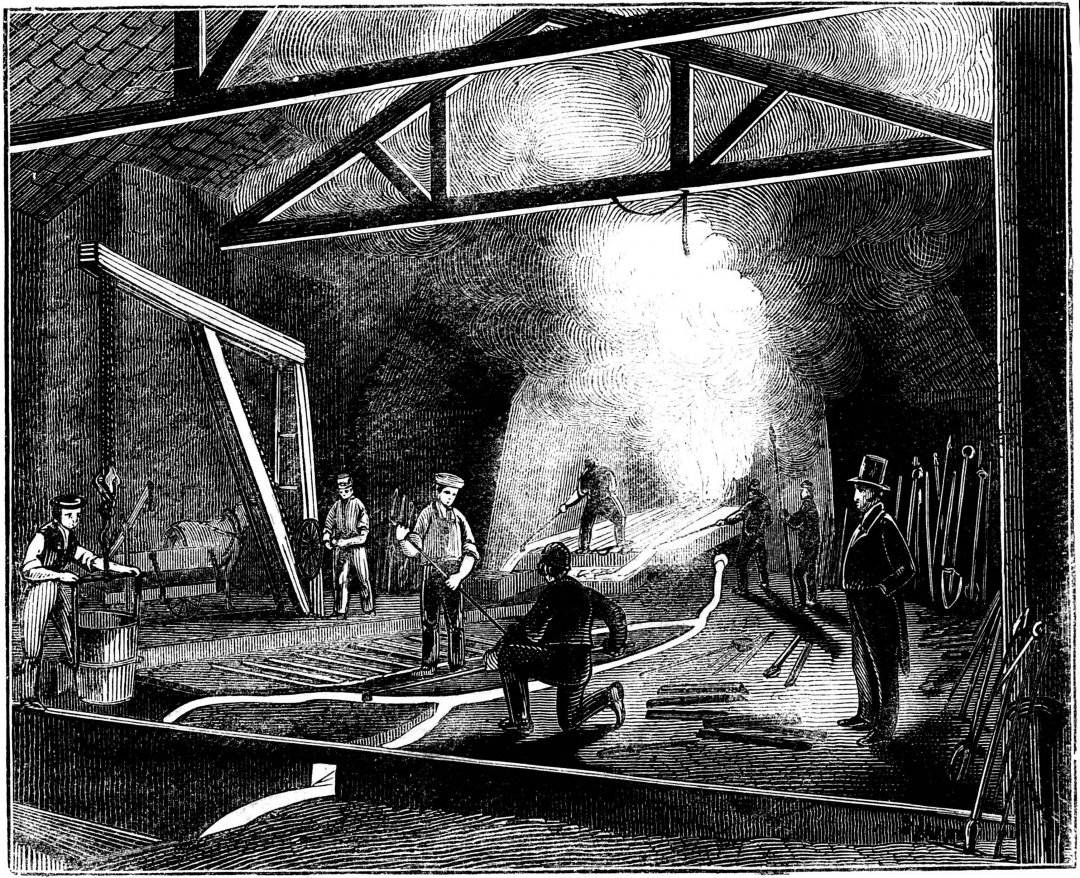

At Ambergate, the boundary takes in the site of an iron foundry and forge that supplied castings to the cotton mills and the railway bridges over the highway and the River Derwent.

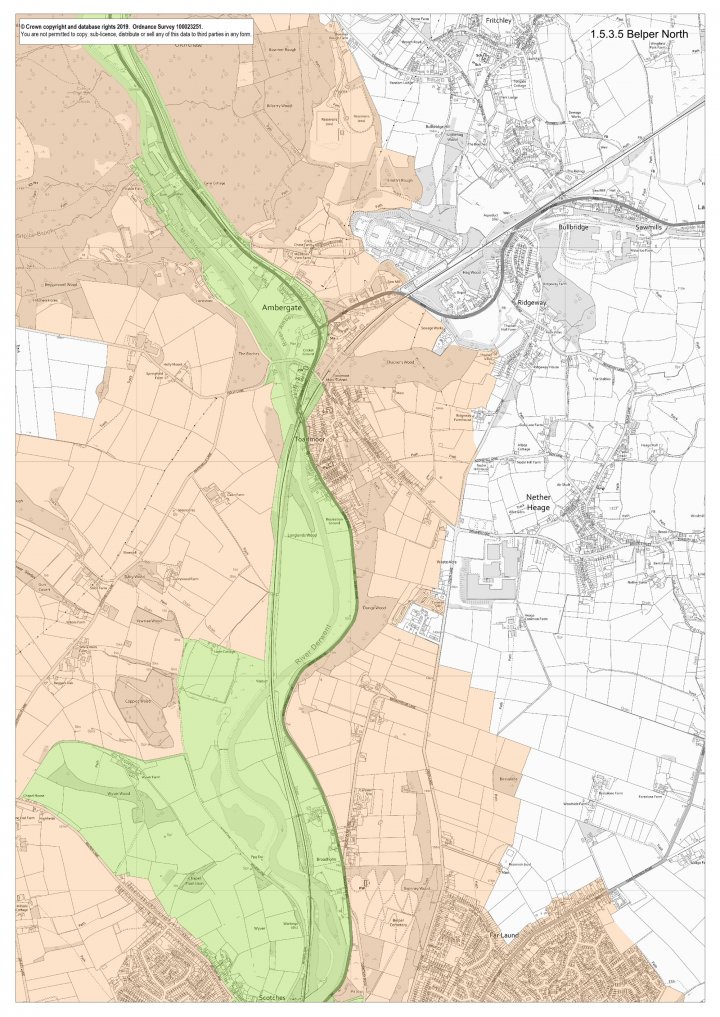

5.3.5 Belper North (Map 5)

The boundaries are formed by the River Derwent and its flood plain to the west and the A6 road to the east until the Belper Conservation Area is reached. Strutt’s Wyver Farm lies in the west of the area.

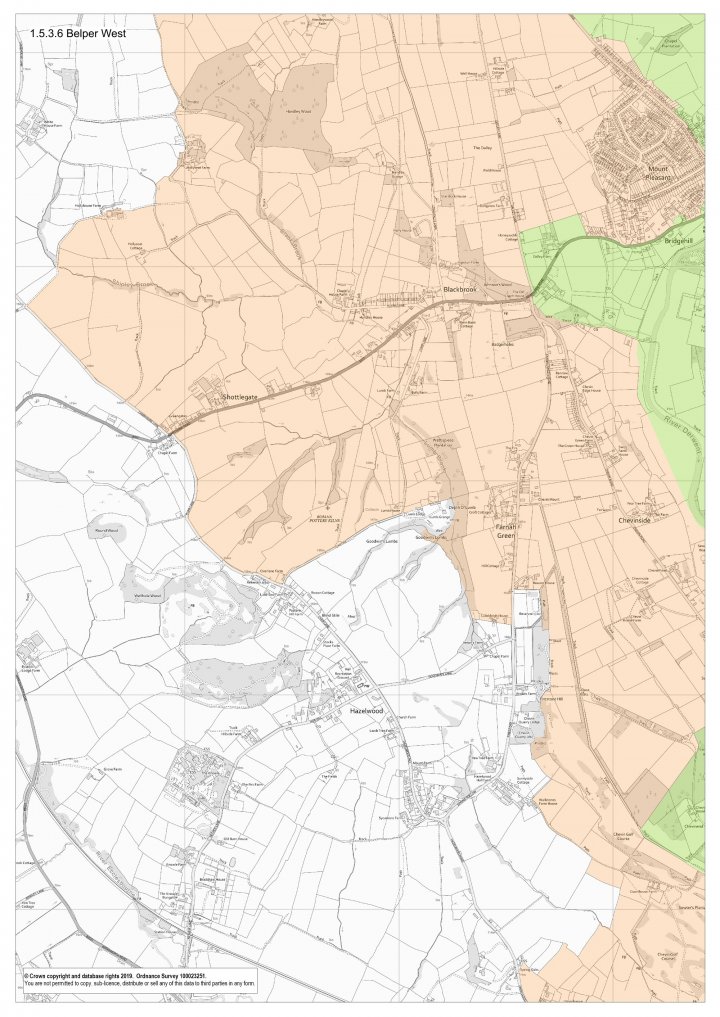

5.3.6 Belper West (Map 6)

The site incorporates Strutt’s Dalley and Crossroads Farms. The Buffer Zone extends out to another Strutt farm, Shottlegate.

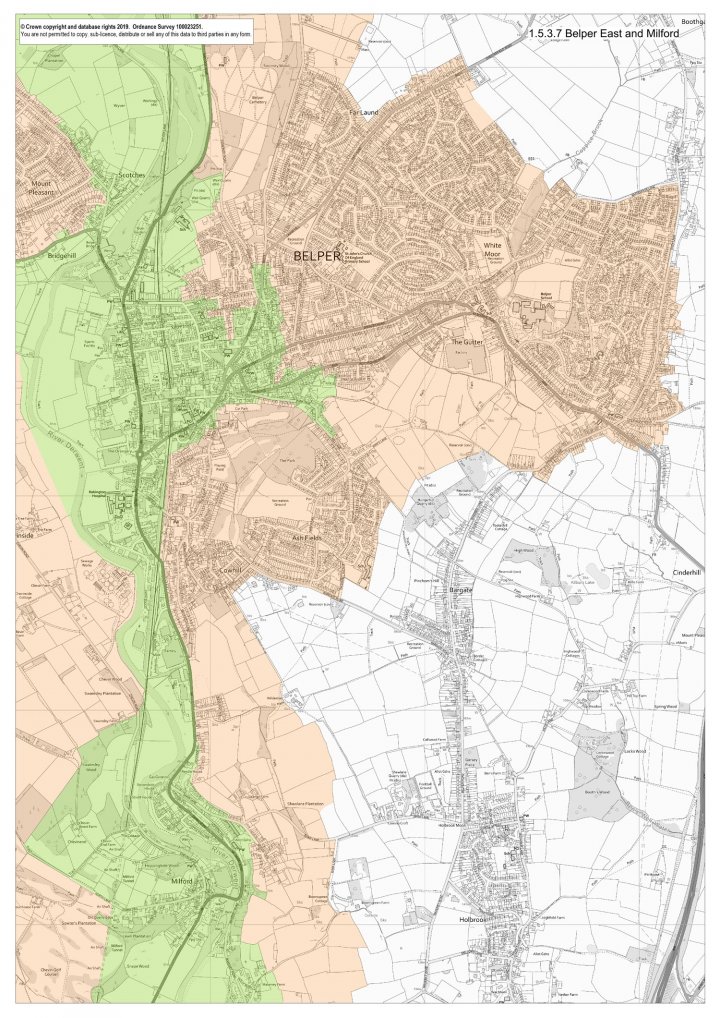

5.3.7 Belper East and Milford (Map 7)

The site incorporates the Belper and Milford Conservation Area2 except for the remnant of the medieval deer park in the south-east corner, which is omitted. To the south, the river and its flood plain, the railway and the former Derby-Chesterfield turnpike road, now the A6, contain the area as far as Milford, where the Conservation Area forms the site boundary apart from a minor extension to the west to include the ground above Milford tunnel.

2 The Belper Conservation Area and the Milford Conservation Area were extended on 16 July 2003, with land in between the two designated areas being included, thereby forming one single designation – The Belper and Milford Conservation Area .

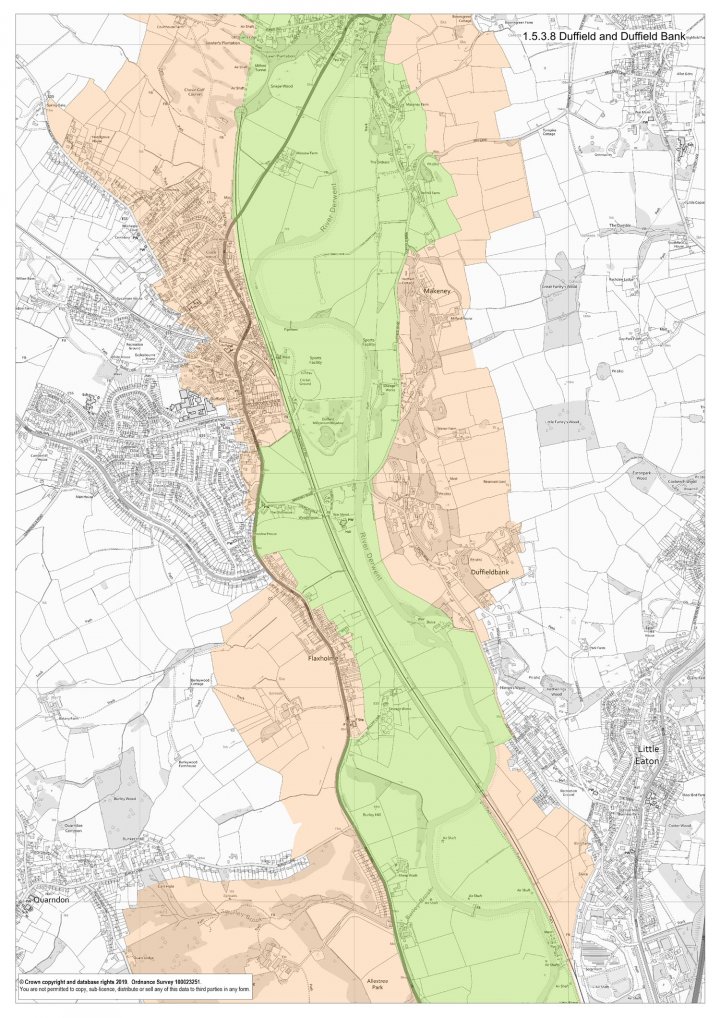

5.3.8 Duffield and Duffield Bank (Map 8)

The boundary follows the flood plain of the River Derwent to the east and keeps close to the road and railway line to the west. The roadside development at Duffield is excluded. The flood plain includes Peckwash Paper Mill at Little Eaton.

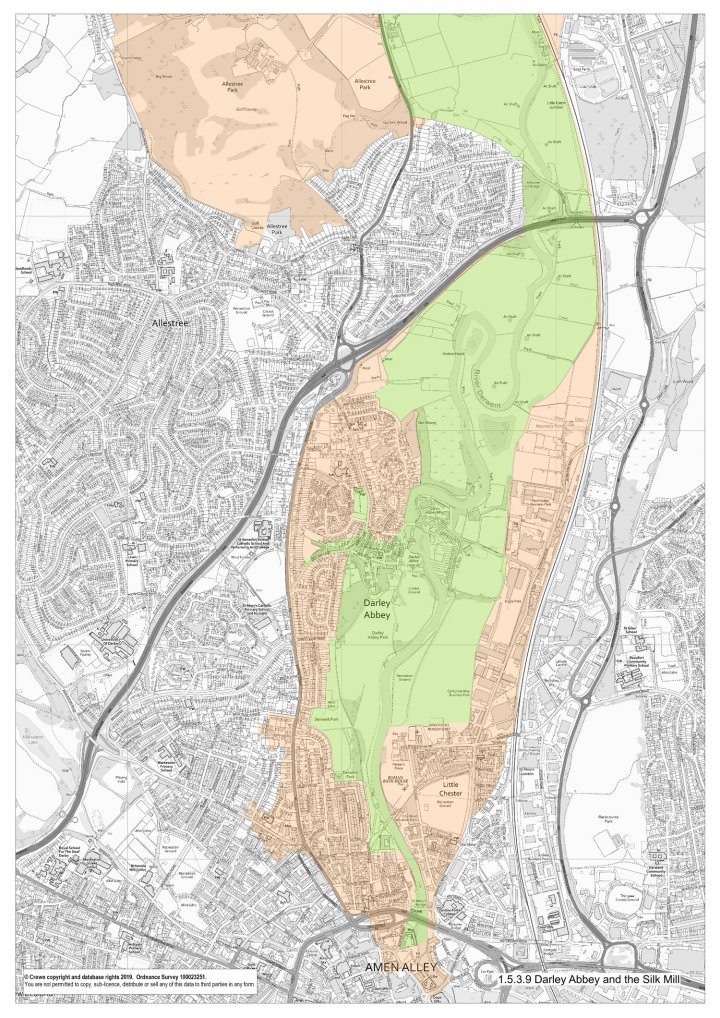

5.3.9 Darley Abbey and the Silk Mill (Map 9)

The whole of the Darley Abbey Conservation Area is included, with an extension to the north to incorporate St Matthew’s Church. All the Evans’ mill complex and factory village are within the site. The river plain forms the eastern boundary, with Darley Abbey Park to the west, formerly part of the Evans’ estate. From Darley Abbey the site narrows as it enters Derby. The River Derwent flood plain to the east and Derwent Park to the west form the boundaries until the river alone carries the site to its southern extremity, Derby Silk Mill.

5.4 The Buffer Zone

The Buffer Zone has been defined in order to protect the site from development that would damage its setting. Some attributes that relate to the primary significance of the site are included. Wherever possible, boundaries of existing protected areas (e.g. Conservation Areas and Green Belt) have been adopted. The Landscape Character Assessment for Derbyshire also informed the definition of the buffer zone.

The boundary of the Buffer Zone is generally clearly evident on the ground by virtue of easily identifiable features, such as field boundaries, watercourses or roads.

In the north, where the relief of the topography is marked, a skyline to skyline approach has been adopted.

In the Belper area the Buffer Zone encompasses, to the west, the historic farmland of the Strutts. To the east, where the ground rises, the limits of the settlement and the green belt boundary have been used. To the south the Buffer Zone is defined by field boundaries just below the skyline.

At Duffield, the Buffer Zone comprises the Duffield Conservation Area to the west and, to the east, the rising ground of Duffield Bank and Eaton Bank, including Eaton Bank Conservation Area. Further south the landscaped park of Allestree Hall, the former home of William Evans, provides the Buffer Zone on the western side.

At Darley Abbey, the Buffer Zone consists of the rising land up to the A6 and A38 roads to the west and the land abutting the River Derwent’s flood plain up to the railway to the east. Further south it includes the Strutt’s Park Conservation Area, the Chester Green Conservation Area, part of the River Derwent immediately south of the site and Derby Cathedral.

It should be noted that the Buffer Zone does not and cannot incorporate the complete setting of the World Heritage Site, which is wider. Development within the broader setting will need to be considered on a case-by-case basis as to impacts on Outstanding Universal Value, particularly if they are of a large scale, either in number or height of buildings or structures (e.g. wind turbines), or exceptionally tall relative to their context (the latter being a particular concern at the southern end of the World Heritage Site, within the setting of the Derby Silk Mill).

The Buffer Zone does include attributes which are functionally linked to the World Heritage Site, particularly the relict landscape, ‘arrested in time’ (see 1.3), and give an essential context in which the World Heritage Site’s Outstanding Universal Value can be understood.

5.5 Historic Context of the Site

The eighteenth century witnessed a fundamental restructuring of economic organisation within society, resulting in the major landmark in human history that came to be known as the ‘Industrial Revolution’. Amongst its many innovations was the successful harnessing of relatively large amounts of natural energy to deliver the mechanical power needed to drive machines housed in mills producing goods at an unprecedented rate.

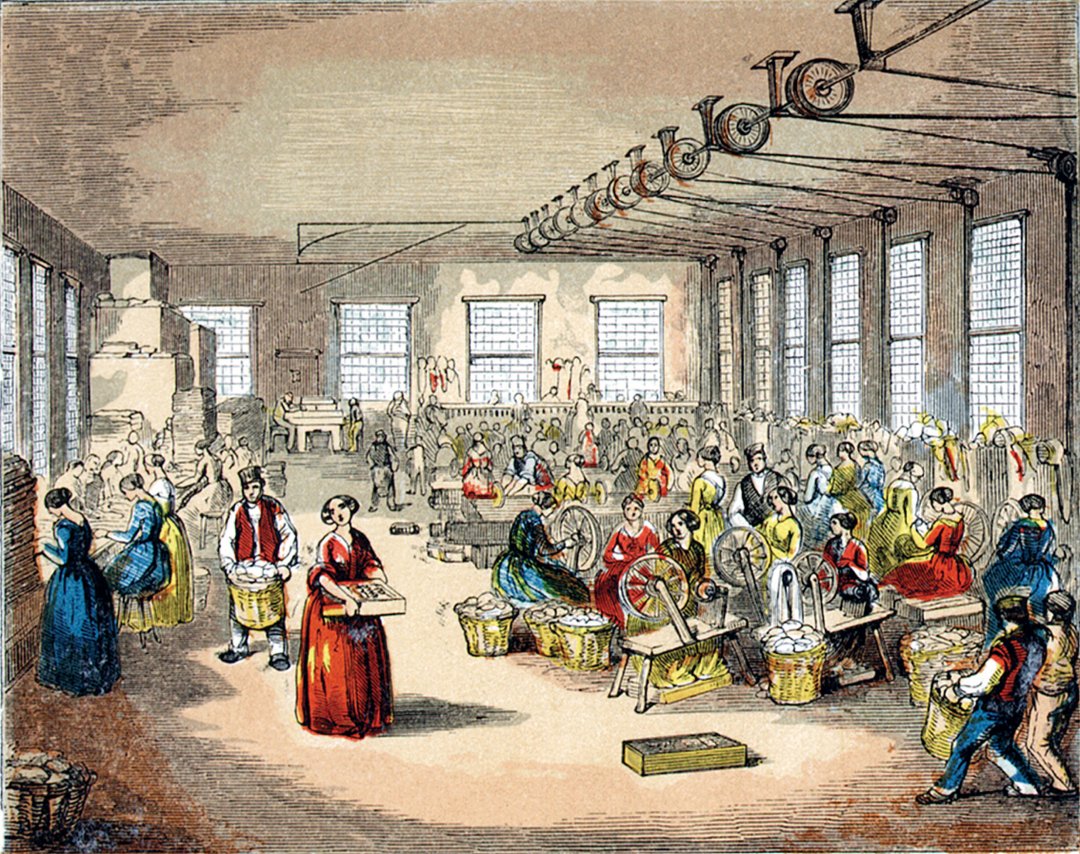

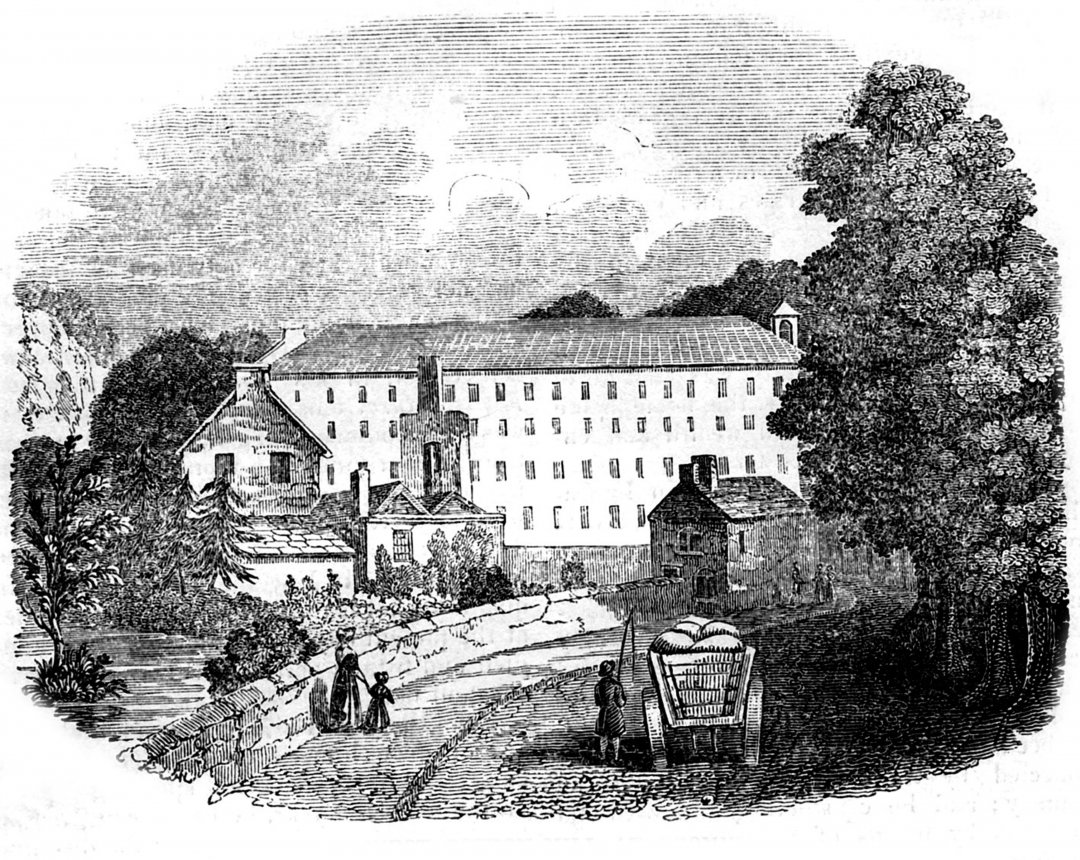

The first stages in the establishment of this new system, the factory system, occurred in the Derwent Valley. At its southern end is the Lombe brothers’ Silk Mill in Derby which, when it opened in 1721, brought to England technology developed in Italy which enabled silk to be thrown on machines driven by water power. This important step towards full-scale factory production did not on its own trigger rapid or widespread economic investment in mechanised production, but its influence on the later developments in the cotton industry which took place a few miles to the north, at Cromford, is now widely recognised.

It was Richard Arkwright’s Cromford Mill that provided the true blueprint for factory production. Arkwright’s system was copied widely in many parts of Britain and, soon after, across the globe.

The structures that housed the new industry and its workforce, and the landscape created around them, remain. Overall, the degree to which early mill sites in the area have survived is remarkable. The value of Cromford in the World Heritage Site is further enhanced by the survival of the settlement that was constructed contemporaneously with the industrial buildings, to accommodate the mill workers. Cromford was relatively remote and sparsely populated, and Arkwright could only obtain the young people he required for his labour force if he provided houses for their parents. In Cromford, there emerged a new kind of industrial community that was copied and developed in the other Derwent Valley settlements.

Arkwright’s activities stimulated a surge of industrial growth in the Derwent Valley. His close association with the entrepreneurs Jedediah Strutt, Thomas Evans and Peter Nightingale set in train a series of important developments along the valley. All were successful industrialists, whose economic interests extended well beyond cotton manufacturing. They were also enlightened employers who displayed a strong sense of responsibility for their workforce, their dependants and for the communities that came into being to serve the new industrial system. As such, the developments at Belper, beginning in 1776, at Milford from 1781, and Darley Abbey from 1782, provided early models for the creation of industrial communities.

Today, the housing and infrastructure in these settlements, which were brought into being by the same economic and industrial opportunities and constraints as Cromford, offer unique possibilities for comparison and analysis. In each case, there has been a high degree of survival and the number of houses of an early date, the range of the house types and the extent of the community infrastructure, are the components of an archive of bricks and mortar of unparalleled importance. Nowhere outside the Derwent Valley does the physical evidence of the early factory community survive in such abundance.

The manufacture of cotton thread continued to prosper in the Derwent Valley through the nineteenth century at a level that was sufficient to maintain the mills and their communities. Some extensions were built, especially after the formation of the English Sewing Cotton Company in 1897, e.g. at Masson Mill and at Belper, with the construction of the East Mill.

Survival depended upon specialisation and the manufacture of sewing thread for industrial and domestic purposes replaced their earliest function as spinning mills.

Redirection of production to domestic sewing thread maintained the mills until the 1980s (Belper) and 1990s (Masson and Milford).

As the heart of the textile industry moved to Lancashire and Cheshire, the Derwent Valley became a relative backwater. This was particularly the case at Cromford, where a combination of topographical constraints and inaccessibility limited the possibility for growth.

Had the Derwent Valley rather than Manchester become ‘Cottonopolis’, there would have been a serious risk of these earlier settlements being over-run and their monuments lost, overwhelmed in the name of economic development.

As it was, though, Derby itself remained a market and mill town until the second half of the 19th century when the railway industry led to a second phase of industrial expansion. Further industrial growth and escalating urbanisation did not engulf the valley north of Derby. The original late 18th and early 19th century mills and the community infrastructure have survived within a largely unaltered landscape. The cultural landscape created by the factory system remains substantially intact.

5.6 Cultural Landscape

In 1992 the World Heritage Convention became the first international legal instrument to recognise and protect cultural landscapes, adopting guidelines concerning their inclusion in the World Heritage List. Although the Derwent Valley Mills was not inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2001 as a ‘cultural landscape’, it displays many of the characteristics of this category.

A prerequisite for the protection and enhancement of the site’s ‘cultural landscape’ is an understanding of what is meant by that term and also what constitutes the nature and qualities of this particular cultural landscape.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has defined cultural landscapes as “representing the combined works of nature and man”. Of course very few landscapes in the world, and certainly in the United Kingdom, are not of this nature. But it is a useful term to describe the lower Derwent Valley, whose character is very much determined by the way men and women have sustained themselves and their families by the production of goods through harnessing the river’s power, by the mining and processing of minerals from the underlying rocks, by the management of woodland and by cultivation of the soil.

The document which nominated the site to UNESCO explains how the landscape’s particular character is the result of “arrested urbanisation”. Whereas the urbanisation continued unabated in Lancashire, following the initial revolutionary phase of industrial innovation, in the Derwent Valley growth was much reduced in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The whole of the World Heritage Site is a relict landscape where the natural relief and flora has been extensively modified by human intervention, the evidence for which is sometimes obvious, but often not.

For most of the length of the site the presence of the river itself is the constant factor. Above the riverside meadows, within the wider buffer zone of the World Heritage Site, the landscapes of the Peak Fringe are diverse and contrasting. The majority of the buffer zone is defined by the organic landscape of wooded slopes and valleys.

5.6.1 Landscape Character

The Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site, as the name suggests, falls completely within the valley of the River Derwent. With steep, wooded valley sides in the north, the flood plain broadens towards Duffield, with the Derwent meandering throughout it. In the north, smaller fast-flowing brooks were dammed to harness water power for the textile mills.

This early industrialisation was largely arrested due to competition elsewhere, so that land-use has remained predominantly pastoral with mixed stock rearing and rough grazing, and some mixed farming with occasional arable fields where topography allows.

Woodland is well represented, with extensive ancient semi-natural woodland occupying steep valley sides and smaller woodlands elsewhere.

Towards Derby the heavy soils and the vulnerability of the river meadows to flooding led to the early abandonment of arable farming, leaving evidence of medieval ridge and furrow around Duffield and Allestree. At Duffield ornamental parkland extends into the landscape and generally the proximity of Derby becomes progressively more apparent. The expansion of Derby is slowly introducing urban fringe activities into an otherwise agricultural landscape. Beyond Darley Abbey the riverside meadows lose all semblance of nature, being manicured into parkland and playing fields until they are contained between urban development within the city centre.

5.6.2 Archaeology and Early History

The Derwent Valley links the Trent Valley with the uplands of the carboniferous limestone and gritstone moors of the Peak District. The long-standing historic importance of the Derwent is indicated by its name being of Celtic origin. The Romans established a fort, Derventio, at Little Chester, a kilometre north of the present city centre of Derby. It became the hub of a road network, enabling it to become a market and administrative centre.

Throughout the Middle Ages the lower Derwent Valley remained a quiet provincial backwater. The only monastic foundation was at Darley Abbey. Gradually, the exploitation of local natural resources resulted in the development of modest industrial activities, especially cloth-making, metal smelting and casting. Derby became a centre for these activities and, by the 18th Century, formed part of the East Midlands ‘textiles triangle’, which included Nottingham and Leicester. Economic development in the Derwent Valley itself, though, was inhibited throughout this period by poor transport links.

5.6.3 The Industrial Revolution and the Valley’s architectural heritage

In this remote area an industrial economy emerged and flourished. The River Derwent and its tributaries were crucial in providing the waterpower that underpinned the growth of textile manufacture and the various metal, paper and mineral based industries which were colonising the Valley. Gradually, communications improved, through the construction of turnpike roads and, more emphatically, through the opening of the Cromford, Erewash and Derby Canals, which linked the area to the national transport system. The area for which the canal provided transportation was much greater than the canal corridor, being extended by a network of rail tramways. These were horse drawn. In 1826 an Act of Parliament made possible construction of the Cromford and High Peak Railway which linked the canal to Whaley Bridge and the north west of England.

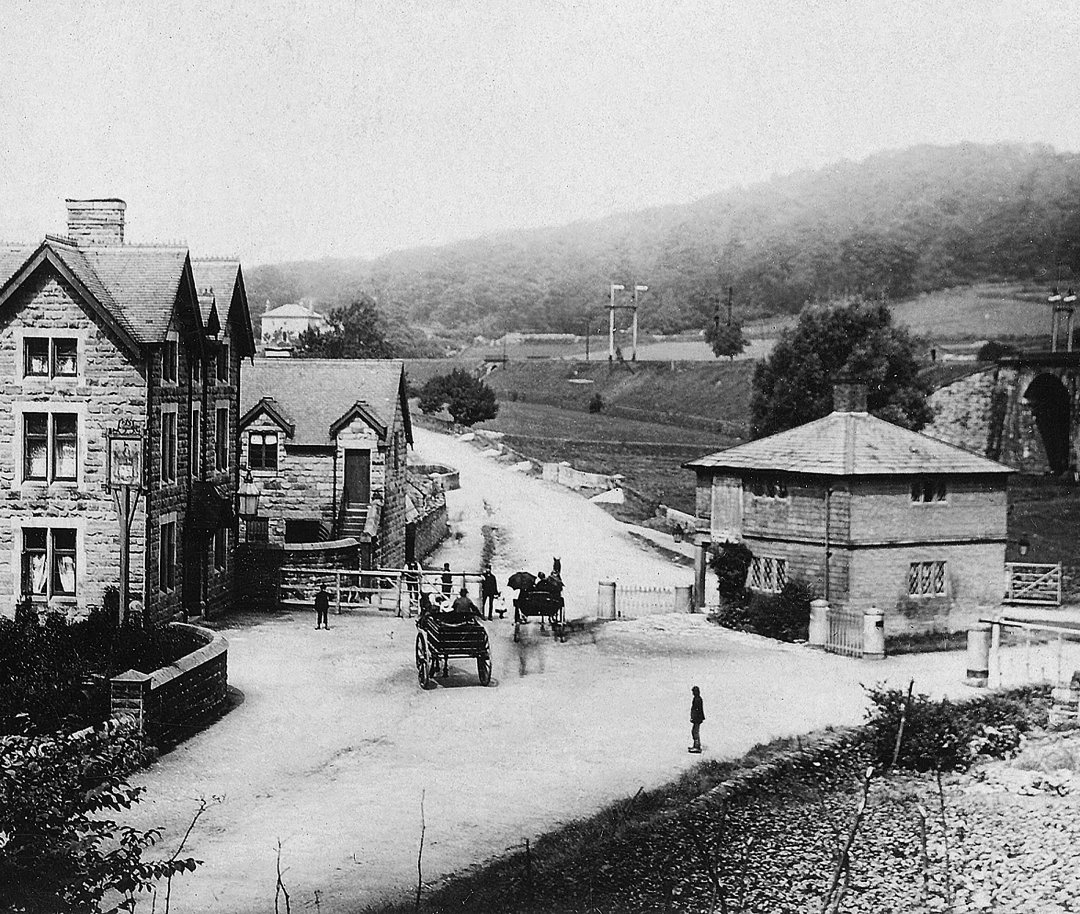

On elevated causeways above the flood plain runs the railway which ultimately superseded the canal, with the riverside road, now the A6, which largely follows the line of two turnpike roads connecting Cromford, Belper and Derby. These braided lines of transportation form the spine of the World Heritage Site and constitute one of the most important elements of the cultural landscape. Views of the site obtained from the road and the railway line are of particular importance. This sequential experience of views, travelling north to south or vice versa, is what constitutes for most visitors, and even residents, their principal experience of the site.

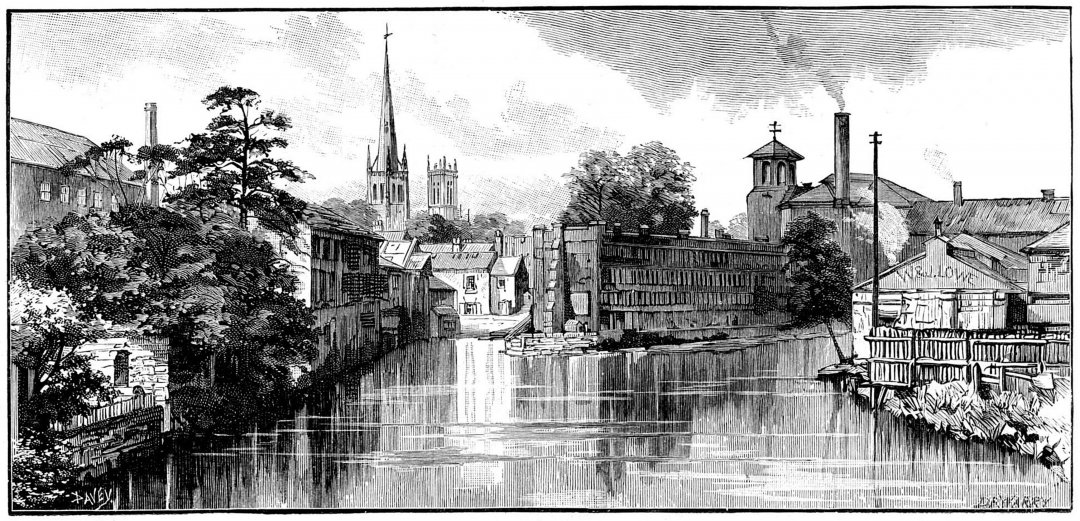

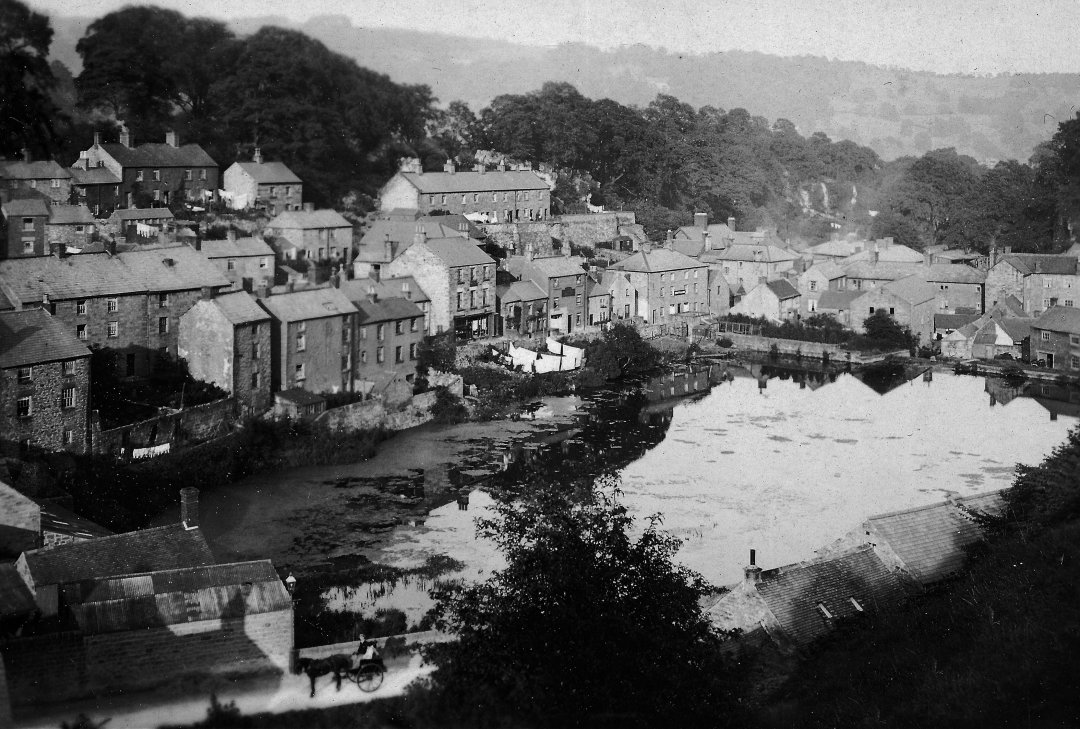

The sustained economic investment in industrial development between the 1770s and the middle of the 19th Century changed the face of the lower Derwent Valley. Around long established hamlets and small villages new settlements emerged. None was more successful than Belper, which grew to a size of such economic importance that it superseded Wirksworth, traditionally the area’s second town. After the 1830s, the new Poor Law Union established its workhouse and administrative offices, and Belper became in effect the seat of local government for a wide area.

Derby, unassailably the county town, retained its market and administrative function, but added from an early date a strong industrial and commercial base. The town’s wealth and self-confidence found expression in the elegant Georgian and Regency houses, some of which survive, around the Cathedral and the Silk Mill.

Further north in the Valley, the same industrial and landed wealth bequeathed a clutch of imposing and comfortable houses constructed by the business men, professionals, landowners and, above all, the new industrial and commercial entrepreneurs.

Of those that have survived, Willersley Castle, Sir Richard Arkwright’s family mansion, is the most opulent and notable example. However, such houses and their estates and the large farms often associated with them are not the Valley’s principal architectural legacy of its industrial past. This distinction belongs to the mills, their millponds, weirs and watercourses and to the mill-workers’ cottages that accompany them. The terraces and groups of houses in the Derwent Valley factory settlements are not the work of known architects but they exhibit a superior quality of design which derives both from local vernacular tradition and from an appreciation of Georgian style and proportions.

The buildings and structures related to the Cromford Canal and the North Midland and the Manchester, Matlock, Buxton, and Midlands Junction railways, are examples of some of the earliest architecture of the new modes of transport in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, which served the Valley’s industrial complexes. The North Midland Railway engineering structures also provide the finest surviving examples of the Stephensons’ influence on railway construction.

Growth of the cotton mill communities in the early years of the 19th century generated the building of schools, chapels and churches and, later in the century and early in the 20th century, other community facilities, such as the district workhouse, public baths, a police house, a cemetery and public parks. Many of the new facilities were initiated and financed in whole or in part by the mill owners. Complimentary industries also flourished, including hosiery/ framework knitting.

Some of the most arresting farmsteads in this landscape are those built by the Strutts, who employed innovative building techniques developed for the construction of their mills and highly organised modes of processing feed and animal waste, which influenced the layout and appearance of the farm complexes.

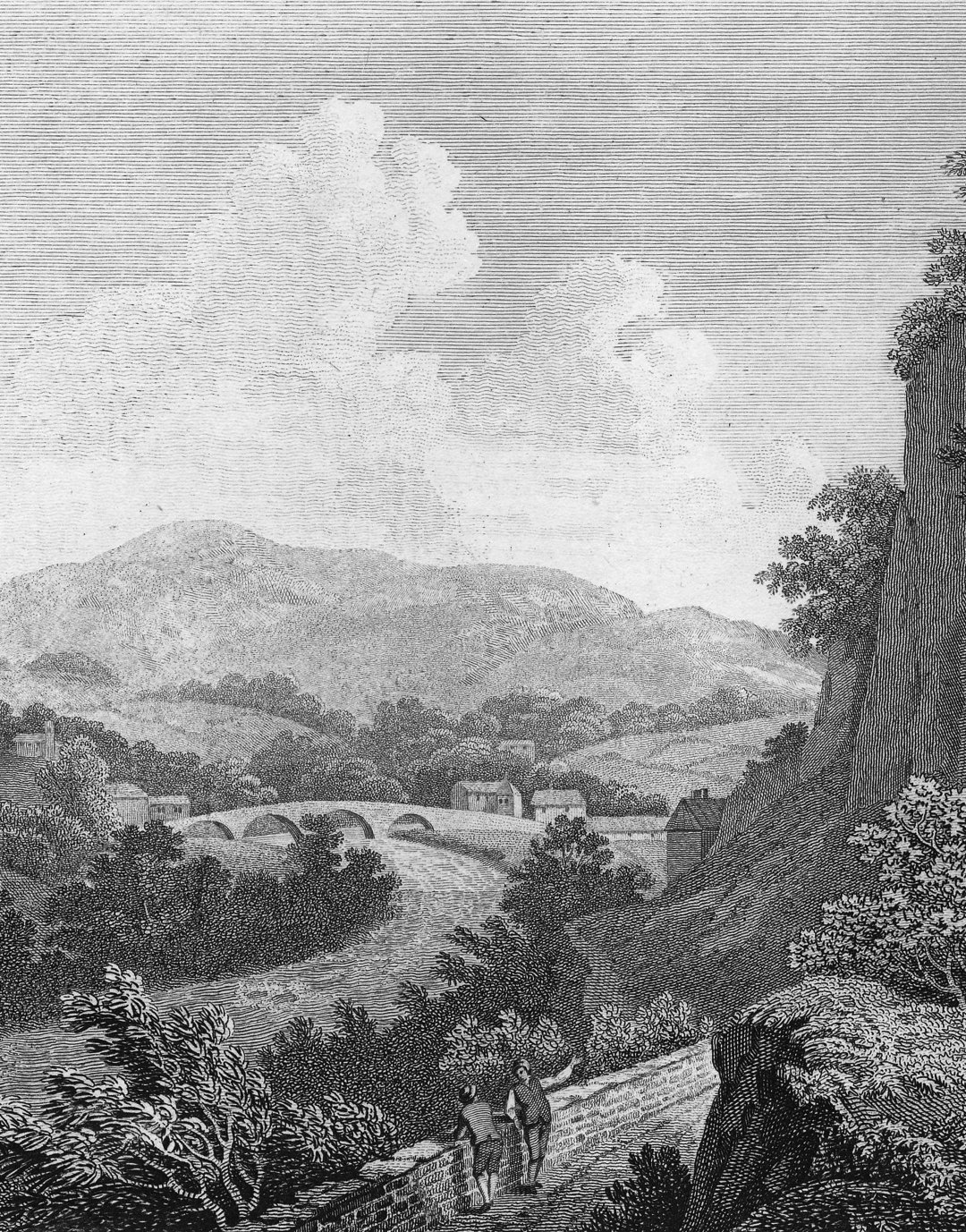

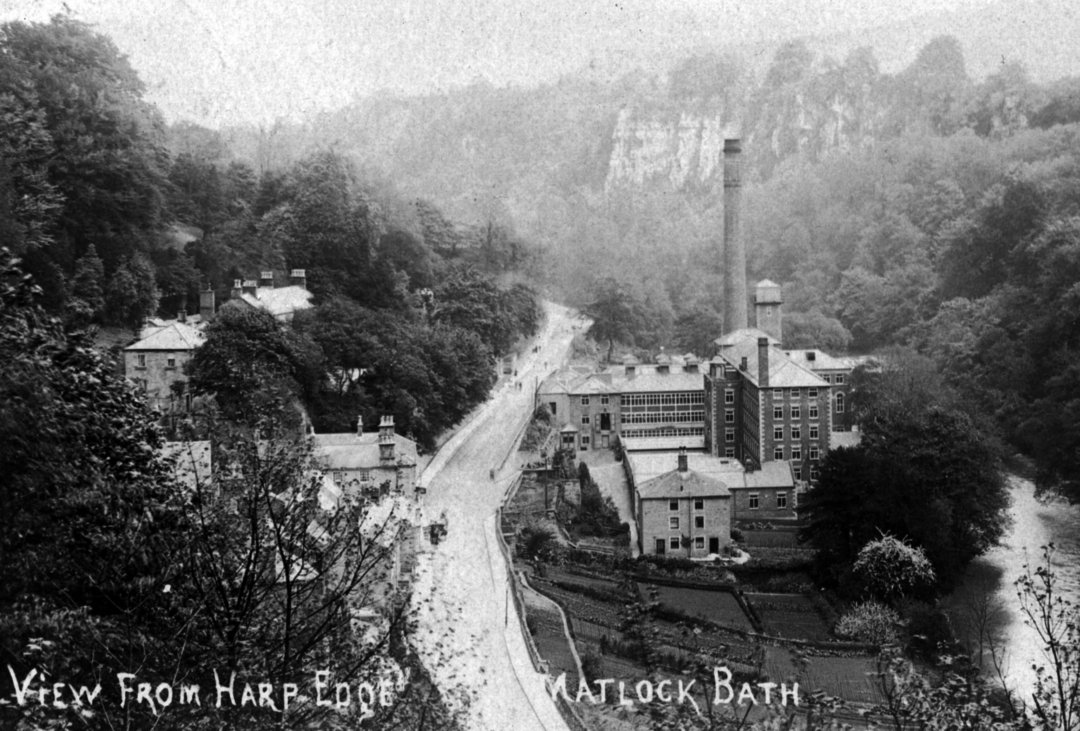

Because of the slowing of urbanisation in the valley by the end of the 19th century, the setting of many of the buildings was largely preserved. In many cases the building’s architectural heritage is enhanced by landscape setting and in Cromford and Matlock Bath by the dramatic and picturesque scenery of the Matlock Gorge.

5.6.4 Geology

The geology of this part of the Derwent Valley consists mostly of rocks from the Carboniferous Series. In the north, around Cromford and Matlock Bath, the hard, resistant carboniferous limestone produces rugged upland scenery through which the River Derwent carves a dramatic narrow gorge. The limestone rock in this vicinity is faulted and folded and contains bands of volcanic basalt and mineralised veins which are the source of ores of lead, zinc, barium and fluorine.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century the limestone gorge between Matlock and Cromford was admired for its picturesque and “sublime” qualities. The choice of design for Masson Mill demonstrated a desire to honour these qualities. Even though it has lost some of its wild grandeur the gorge continues to attract visitors by virtue of its drama and beauty. Views into and out of the site are particularly important at this northern extremity.

Further south the carboniferous limestone is overlain by millstone grit of the same series which consists of fairly soft shales interspersed with hard layers of coarse sandstone grit locally known as gritstone. Gritstone outcrops on both sides of the Derwent as far south as Little Eaton provide steep-sided hills and create a well-defined, enclosed valley. The gritstones are a source of high quality building stone.

Just north of Derby the Carboniferous Series is abruptly replaced at the surface by the Triassic Sandstone Series, mainly soft marlstones and harder red or pink sandstones. The latter produce a distinct low ridge to the west of Darley Abbey.

There are five Regionally Important Geological Sites, identified in Local Plans for protection.

5.6.5 Ecology

The northern end of the World Heritage Site lies within the White Peak Natural Area with the distinctive Carboniferous limestone features mentioned above. The underlying geology and soils here have given rise to rich habitats for wildlife, particularly in woodlands found in the steep sided ravines. Two such woodlands, Slinter Wood and Hagg Wood, are located within the World Heritage Site, and are both within Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). These woodlands are two of the best examples of ancient ash woodland on limestone in Derbyshire and, together with metallophyte (metal tolerant plant) communities, support a number of scarce plants of national importance. The low-fertility grasslands on carboniferous limestone include the Rose End Meadows SSSI in the buffer zone to the north of Cromford.

The Derbyshire Peak Fringe and Lower Derwent Natural Area encompasses the rest of the World Heritage Site to the south. The gritstone provides acidic soils and the steep valley sides, with the Derwent’s liability to flood, create a complex of habitats. The woodlands, primarily oak and birch with flushed wetland areas, are of particular importance. Shining Cliff Woods, in the buffer zone to the west, is also a SSSI.

Grassland is the dominant habitat throughout the WHS, particularly from just north of Belper where the valley floor widens southwards. Riverside grasslands are extensive but little remains of the former traditional lowland, the unimproved hay meadows. The Derwent is an important habitat, flowing the length of the World Heritage Site with adjacent marshes and wet grassland. The Cromford Canal, and some of its towpath, is a SSSI.

Sixteen Wildlife Sites are identified by the Derbyshire Wildlife Trust as either wholly or partly within the WHS. These are identified in Local Strategic Plans for protection.

5.6.6 Landscape

The Industrial Revolution inevitably brought about many changes. Textile mills and industrial settlements, waterpower systems, turnpike roads and canals and, later, railways, all changed the landscape. Farming was intensified through the adaptation of mass production techniques developed in the mills. The River Derwent was tamed – up to a point – by engineering works, and woodlands were reduced and quarries dug into hillsides to provide building materials. Even so, by the middle of the 19th century, with the exception of Derby, and to a lesser extent Belper, this had become an area of ‘arrested urbanisation’. As a result, most of this stretch of the Derwent Valley retains a rural or semi-rural appearance. Most of the hills, particularly the steeper slopes, remain wooded; in some cases the woodland characteristics have been influenced by past management associated with local industries e.g. Crich Chase where ancient coppiced oaks are a legacy of white coal making for lead smelting which dates back to the 16th century, possibly earlier.

Some sections of the valley, particularly between Ambergate and Cromford, are almost entirely rural in character. Much of the surviving elaborate waterpower infrastructure of ponds, weirs and leats for the mills now provides tranquil aquatic habitats, as does the stretch of the canal running south from Cromford to Ambergate. Quarries are now disused and have merged into the natural landscape to form habitats of a distinctive variety. The same is true of the spoil heaps of abandoned lead workings on the northern edge of the area, which support rare species of plants tolerant to the otherwise toxic ground conditions.

This stretch of the Derwent Valley contains a large number of protected areas of landscape and wildlife habitats. Most of the rural area of the valley north of Milford is classified as a Special Landscape Area in the statutory local plans, which is the highest quality of landscape that is designated in Derbyshire outside the Peak District National Park.

Some of the ‘rural’ landscape within the valley is the direct result of the mill owners preserving but also adjusting and shaping their surroundings so it better worked for their industrial purposes but also retained or established attractive views from their homes. For example at Belper, whilst the town faced away from the river, the water meadows were utilised by George Benson Strutt to create a parkland setting to the house he built for himself on the hillside above the mills in 1793. Later a private carriage drive was created through this parkland to make the most of the riverside setting.

The fortitude of these pioneer industrialists, to create a landscape which worked for them, is now so embedded as to be misconstrued as a ‘natural landscape’. This shaping of the valley is an important contributory factor to the nature of the landscape today, and its contribution to the Outstanding Universal Value of the Derwent Valley Mills.

Later philanthropic activity by George Herbert Strutt, the great-great-grandson of Jedediah Strutt, saw the creation of Belper River Gardens as a recreational space and attraction for the residents of Belper and the wider region. This garden is now included on Historic England’s Register of Historic Parks and Gardens and has a Grade II listing.

The Belper cemetery, although not developed by the Strutts, once established, became the resting place for the family. Indeed, some earlier members of the family were re-interred in the cemetery to encourage greater acceptance of the cemetery by Belper residents.

The cemetery was laid out by William Barron, who was a prominent landscape designer/gardener from Scotland who relocated to Derbyshire in the first half of the 19th century. It is included as a Grade II* entry on Historic England’s Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.

5.6.7 Complementary Cultural Stories

The landscape surrounding the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site and its Buffer Zone contains many complementary or associated stories which relate to the core narrative of the Site’s Outstanding Universal Value. These, not exclusively, include early tourism spa developments at Matlock Bath; the development of framework knitting in the Belper area; the development of early industries using the power of the river such as lead smelting and iron forges; the ironworks developed by the Butterley Company near Ripley; and railway expansion and the arrival of Rolls-Royce at Derby. The Derwent Valley Mills sit within an area of Derbyshire which is rich in industrial heritage and value.

5.7 Economic Development

5.7.1 Transport developments

The economic development of the area was originally based upon local natural resources: agricultural (especially wool and dairy), mineral (especially lead, iron-stone, limestone, gritstone, coal and clay) and waterpower, from the Derwent and its tributaries. Derby has been an important communications centre since Roman times, but the valley northwards, up into the Peak District, suffered from inadequate communications until the early 19th Century. Only the establishment of textile mill complexes brought significant communications improvements. Even then, the building of turnpikes was sporadic, leaving parts of the valley inaccessible.

Derby had good links to the River Trent and the national canal network, via the Erewash, Cromford and Derby Canals (including navigation on the river Derwent between the Derby Canal and Darley Abbey) and this played a major part in the valley’s industrialisation. The north-south road link between Cromford and Belper provided by the turnpike of 1817/18 (the present A6) transformed communications in the valley. Railway penetration of the valley, thanks to the North Midland line linking Derby to Ambergate and beyond as early as 1840, made slower progress further north in the valley. This was extended north through Matlock Bath in 1849. In the 1860s a through route was completed, via Buxton, to Manchester. By then the Derwent Valley had ceased to be at the forefront of industrial progress.

5.7.2 Nineteenth Century Developments

and Growth of Tourism

Throughout the 19th Century, textile manufacturing remained the largest single economic activity in the area, but within the valley different patterns of economic development were experienced. Derby continued to grow and diversify, benefiting from the railway boom of the mid-nineteenth century, when it became a key centre in the developing rail network and in the manufacture of locomotives and rolling stock. By the end of the century engineering in the town had overtaken textiles in importance. At the same time Derby thrived as the county town, though never challenged Nottingham as the regional centre.

To the north, a different form of economic growth flourished. Matlock Bath grew as a spa resort for an elite clientele, but developed as a day out destination of regional significance for both tourists and day visitors who, from 1849, were brought to the settlement in increasing numbers by the rail link to Derby and other major towns. Matlock Bath, with its hotels and guest houses, refreshment and entertainment facilities, was well placed to receive and accommodate these visitors and experienced steady growth as a result.

Cromford, immediately to the south, was drawn into this tourist boom only to a minor extent. Visitors from Matlock Bath walked through the grounds of Willersley Castle, and enjoyed the beautiful Via Gellia, but the village did not develop a tourist infrastructure. It remained an industrial settlement with Arkwright’s mills at Matlock Bath and Smedley’s Mill at Lea Bridge providing much of the employment, supplemented towards the end of the century by the growth of quarrying and mineral workings in Wirksworth, Middleton and Hopton.

Further south, Belper enjoyed buoyant economic and population growth. Textile and hosiery manufacture, pioneered there by the Strutts, Wards and Brettles, prospered, but there were also engineering and iron-founding. The long local tradition in nail-making flourished until about 1870 when machine-made nails superseded the hand-forged product. The coalfield, to the east of the town, also brought employment and accelerated growth. By the end of the century Belper emerged with an unusually diverse manufacturing economy for its size. This included the rejuvenation of the mills, provided by the formation of the English Sewing Cotton Company.

Even as late as 1835, Andrew Ure in his The Philosophy of Manufactures described the special nature of the setting of the Strutt mills at Belper and Milford in the Derwent Valley, compared to industrial sites elsewhere. On pages 343 and 344, talking of the Strutt mills in Belper, he states: The mills there, plainly elegant, built also of stone, as well as their other mills at Millford (sic), three miles lower down the river, are driven altogether by eighteen magnificent water-wheels, possessing the power of 600 horses […] As no steam engines are employed, this manufacturing village has quite the picturesque air of an Italian scene, with its river, over-hanging woods and distant range of hills.

5.7.3 Twentieth Century Developments: Derby

Darley Abbey remained a centre of textile manufacturing but its role as a commuter centre for Derby grew inexorably from the 1930s. This development has increased pressure on open land, including the allotments once provided by the mill owners to encourage their workers in feeding their families.

Throughout the 20th Century, Derby retained a healthily diverse economy. Textile manufacturing remained important, with synthetic fabrics playing an increasingly important role. Engineering, in many forms, has been the city’s major strength, especially following the development of Rolls Royce’s aero-engine division and the opening of the Toyota motor car plant on the south-western edge of the city. Chemicals, ceramics and food processing have also prospered, and remain important. Derby has been, and remains, pre-eminently a manufacturing city.

In the latter half of the 20th Century the service sector provided a growing proportion of the employment market in Derby and its city region. Tourism never played a prominent part, but the final quarter of the last century saw the growth of a greater pride in the city’s heritage and care for its environment. Progressive pedestrianisation of the city centre has made it more pleasant to visit, and the extension of Conservation Area status to the historic core has ensured protection and scope for enhancement of the city’s heritage. The Silk Mill, on the banks of the River Derwent, at the southern end of the World Heritage Site, is in the process of refurbishment into a ‘Museum of Making’ which will celebrate the city’s industrial heritage and long history of entrepreneurial spirit, engaging people as the southern gateway to the DVMWHS.

5.7.4 Twentieth Century Developments: Cromford and Matlock Bath

The rest of the lower Derwent Valley saw substantial economic changes in the twentieth century. Matlock Bath retained its role as a day resort. It has acquired new attractions including a theme park and a cable car, which continue to attract visitors. At Masson Mill, the twentieth century extensions have been converted into a ‘shopping village’ with a multi-storey car park. The original Arkwright Mill has been refurbished as a working textile museum.

In Cromford, the mills had ceased textile production c.1885. By the 1920s, it was back in full occupation, split between the manufacturing of colour pigment and a laundry. By 1979, with increasingly stringent health and safety regulations, the site was no longer suitable for chemical processes and, heavily contaminated and with the buildings in poor condition, it was put on the market. To prevent the site being broken up and sold piecemeal and the buildings destroyed, it was purchased by the Arkwright Society. Over the years, many buildings have been brought back into economic use, made accessible for the public and the site decontaminated. The mills now make a substantial contribution to employment provision in Cromford, with a visitor centre gateway for the World Heritage Site.

The Arkwright family home, Willersley Castle, became an hotel and conference centre. The pleasure grounds and park that surround the castle are included on the Historic England Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.

Mineral extraction has been an important economic activity around Cromford throughout its history, first through lead mining and subsequently in quarrying. By the middle of the nineteenth century, lead mining had ceased to be a significant influence but a mining museum survives at Matlock Bath. The quarrying of limestone is a major local industry. Areas to the west of Cromford have been heavily quarried. This has provided jobs in the locality although it also creates environmental problems, especially with the movement of large lorries carrying aggregates. These have particularly affected the village of Cromford.

5.7.5 Twentieth Century Developments: Ambergate to Milford

Ambergate, Belper and Milford saw continued economic evolution in the 20th century. Textile manufacturing experienced a prolonged contraction but other sectors, especially engineering, chemicals and food processing, remained buoyant.

At Ambergate, the former Hurt-owned iron forges attracted the development of a wireworks, one of the first industrial sites in the UK to be powered by hydro.

Belper was badly hit for a time in the 1980s by the closure of English Sewing Cotton’s operation at East Mill, but the overall economy of the town proved robust enough to absorb this loss in a relatively short time. Since then, other manufacturing firms have re-located out of the town. Textile manufacture in Belper finally came to an end in 2016 with the closure of Courtaulds on the former West Mill site. A grant-funded Townscape Heritage Initiative enabled a number of shopfronts in the town to be restored at the beginning of the 21st century, contributing to the town winning the Government’s Great British High Street Competition in 2014.

The textile mill complexes at Milford and Darley Abbey underwent considerable change in the 20th century, with some demolition and replacement by modern structures at Milford and further industrial development at Darley Abbey, which has now been fully re-energised with the creation of business units and a wedding venue within the mill buildings.

Perhaps the most important economic change affecting these settlements is the extent to which they have been drawn into the economic and employment ambit of the city of Derby. By the end of the 20th Century they were all functioning as commuter settlements, as the traditional industrial nature in the valley bottom waned. Belper and Milford, in particular have experienced this change, with residential satellite communities for Derby reusing former employment sites.

The former mill sites at Belper and Milford (as at Masson) continue to harness the power of the river and supply the National Grid with Hydro Electric Power.

As with Derby, tourism has so far played a small part in the economy south of Cromford and until recently there was no tourism infrastructure. A modest start has now been made, with a visitor centre and museum at North Mill, Belper, and a restaurant in the mill canteen at Darley Abbey.